The Islamic community has extensively documented the birth of its Holy Scripture. Many books and webpages exist on the subject. To give an example, we can find a reference to the history of the Islamic Scripture, Ahmad Von Denffer wrote an article named ‘Early and Old Manuscripts of the Qur’an and the Printed Qur’an’, April 2006.

History: Early and Old Manuscripts of the Qur’an and the Printed Qur’an

Published: 23.04.2006

History in and of the Qu’ran

Published: 23.04.2006

History in and of the Qu’ran

Ahmad Von Denffer

Source: Ulum al-Qur’an (An Introduction to the Sciences of the Qur’an)

1. Early Manuscripts of the Qur’an

Writing Material

Early manuscripts of the Qur’an were typically written on animal skin. We know that in the lifetime of the Prophet, parts of the revelation were written on all kinds of materials, such as bone, animal skin, palm risps, etc. The ink was prepared from soot.

Early manuscripts of the Qur’an were typically written on animal skin. We know that in the lifetime of the Prophet, parts of the revelation were written on all kinds of materials, such as bone, animal skin, palm risps, etc. The ink was prepared from soot.

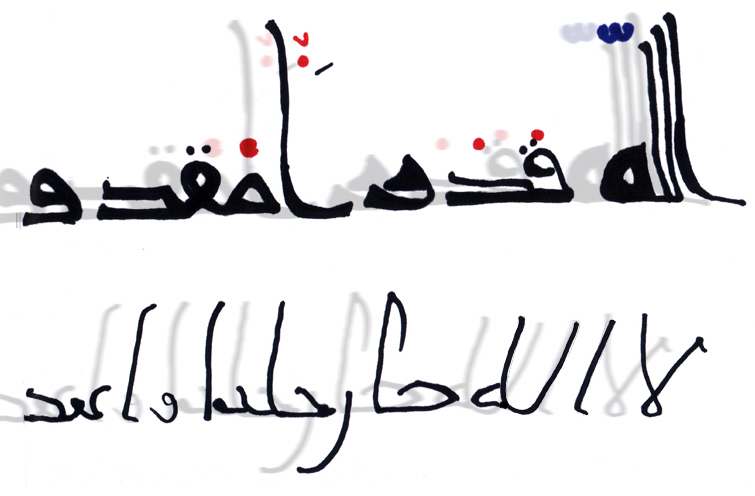

Script

All old Qur’anic script is completely without any diacritical points or vowel signs as explained above. Also there are no headings or separations between the suras nor any other kind of division, nor even any formal indication of the end of a verse. Scholars distinguish between two types of early writing:

All old Qur’anic script is completely without any diacritical points or vowel signs as explained above. Also there are no headings or separations between the suras nor any other kind of division, nor even any formal indication of the end of a verse. Scholars distinguish between two types of early writing:

# Kufi, which is fairly heavy and not very dense.

# Hijazi, which is lighter, more dense and slightly inclined towards the right.

# Hijazi, which is lighter, more dense and slightly inclined towards the right.

Some believe that the Hijazi is older than the Kufi, while others say that both were in use at the same time, but that Hijazi was the less formal style. [1]

Some Peculiarities of the Ancient Writing

Numerous copies of the Qur’an were made after the time of the Prophet Muhammad and the Rightly-Guided Caliphs, and the writers of these manuscripts strictly observed the autography of the ‘Uthmanic Qur’an. There are, compared to the usual Arabic spelling, some peculiarities. Here are a few of them, only concerning the letters alif, ya’, and waw, by way of examples: [2]

Numerous copies of the Qur’an were made after the time of the Prophet Muhammad and the Rightly-Guided Caliphs, and the writers of these manuscripts strictly observed the autography of the ‘Uthmanic Qur’an. There are, compared to the usual Arabic spelling, some peculiarities. Here are a few of them, only concerning the letters alif, ya’, and waw, by way of examples: [2]

# The letter alif is often written on top of a letter instead of after it.

# The letter ya’ (or alif) of the word is omitted.

# Some words have the letter waw in place of alif.

# The letter ya’ (or alif) of the word is omitted.

# Some words have the letter waw in place of alif.

2. Old Manuscripts of the Qur’an

Most of the early original Qur’an manuscripts, complete or in sizeable fragments, that are still available to us now, are not earlier than the second century after the Hijra. The earliest copy, which was exhibited in the British Museum during the 1976 World of Islam Festival, dated from the late second century.[3] However, there are also a number of odd fragments of Qur’anic papyri available, which date from the first century. [4]

There is a copy of the Qur’an in the Egyptian National Library on parchment made from gazelle skin, which has been dated 68 Hijra (688 A.D.), i.e. 58 years after the Prophet’s death.

What happened to ‘Uthman’s Copies?

It is not known exactly how many copies of the Qur’an were made at the time of ‘Uthman, but Suyuti[5] says: ‘The well-known ones are five’. This probably excludes the copy that ‘Uthman kept for himself. The cities of Makka, Damascus, Kufa, Basra and Madina each received a copy. [6]

It is not known exactly how many copies of the Qur’an were made at the time of ‘Uthman, but Suyuti[5] says: ‘The well-known ones are five’. This probably excludes the copy that ‘Uthman kept for himself. The cities of Makka, Damascus, Kufa, Basra and Madina each received a copy. [6]

There are a number of references in the older Arabic literature on this topic which together with latest information available may be summarised as follows:

The Damascus Manuscript

Al-Kindi (d. around 236/850) wrote in the early third century that three out of four of the copies prepared for ‘Uthman were destroyed in fire and war, while the copy sent to Damascus was still kept at his time at Malatja. [7]

Al-Kindi (d. around 236/850) wrote in the early third century that three out of four of the copies prepared for ‘Uthman were destroyed in fire and war, while the copy sent to Damascus was still kept at his time at Malatja. [7]

Ibn Batuta (779/1377) says he has seen copies or sheets from the copies of the Qur’an prepared under ‘Uthman in Granada, Marakesh, Basra and other cities. [8]

Ibn Kathir (d. 774/1372) relates that he has seen a copy of the Qur’an attributed to ‘Uthman, which was brought to Damascus in the year 518 Hijra from Tiberias (Palestine). He said it was ‘very large, in beautiful clear strong writing with strong ink, in parchment, I think, made of camel skin’. [9]

Some believe that the copy later on went to Leningrad and from there to England. After that nothing is known about it. Others hold that this mushaf remained in the mosque of Damascus, where it was last seen before the fire in the year 1310/1892.’ [10]

The Egyptian Manuscript

There is a copy of an old Qur’an kept in the mosque of al-Hussain in Cairo. Its script is of the old style, although Kufi, and it is quite possible that it was copied from the Mushaf of ‘Uthman. [11]

There is a copy of an old Qur’an kept in the mosque of al-Hussain in Cairo. Its script is of the old style, although Kufi, and it is quite possible that it was copied from the Mushaf of ‘Uthman. [11]

The Madina Manuscript

Ibn Jubair (d. 614/1217) saw the manuscript in the mosque of Medina in the year 580/1184. Some say it remained in Medina until the Turks took it from there in 1334/1915. It has been reported that this copy was removed by the Turkish authorities to Istanbul, from where it came to Berlin during World War I. The Treaty of Versailles, which concluded World War I, contains the following clause:

Ibn Jubair (d. 614/1217) saw the manuscript in the mosque of Medina in the year 580/1184. Some say it remained in Medina until the Turks took it from there in 1334/1915. It has been reported that this copy was removed by the Turkish authorities to Istanbul, from where it came to Berlin during World War I. The Treaty of Versailles, which concluded World War I, contains the following clause:

‘Article 246: Within six months from the coming into force of the present Treaty, Germany will restore to His Majesty, King of Hedjaz, the original Koran of Caliph Othman, which was removed from Medina by the Turkish authorities and is stated to have been presented to the ex-Emperor William II.” [12]

The manuscript then reached Istanbul, but not Madina. [13]

The ‘Imam’ Manuscript

This is the name used for the copy which ‘Uthman kept himself, and it is said he was killed while reading it. [14]

This is the name used for the copy which ‘Uthman kept himself, and it is said he was killed while reading it. [14]

According to some the Umayyads took it to Andalusia, from where it came to Fas (Morocco) and according to Ibn Batuta it was there in the eighth century after the Hijra, and there were traces of blood on it. From Morocco, it might have found its way to Samarkand.

The Samarkand Manuscript

[15] This is the copy now kept in Tashkent (Uzbekistan). It may be the Imam manuscript or one of the other copies made at the time of ‘Uthman.

[15] This is the copy now kept in Tashkent (Uzbekistan). It may be the Imam manuscript or one of the other copies made at the time of ‘Uthman.

It came to Samarkand in 890 Hijra (1485) and remained there till 1868. Then it was taken to St. Petersburg by the Russians in 1869. It remained there till 1917. A Russian orientalist gave a detailed description of it, saying that many pages were damaged and some were missing. A facsimile, some 50 copies, of this mushaf was produced by S. Pisareff in 1905. A copy was sent to the Ottoman Sultan ‘Abdul Hamid, to the Shah of Iran, to the Amir of Bukhara, to Afghanistan, to Fas and some important Muslim personalities. One copy is now in the Columbia University Library (U.S.A.). [16]

The manuscript was afterwards returned to its former place and reached Tashkent in 1924, where it has remained since. Apparently the Soviet authorities have made further copies, which are presented from time to time to visiting Muslim heads of state and other important personalities. In 1980, photocopies of such a facsimile were produced in the United States, with a two-page foreword by M. Hamidullah.

The writer of the History of the Mushaf of ‘Uthman in Tashkent gives a number of reasons for the authenticity of the manuscript. They are, excluding the various historical reports which suggest this, as follows:

# The fact that the mushaf is written in a script used in the first half of the first century Hijra.

# The fact that it is written on parchment from a gazelle, while later Qur’ans are written on paper-like sheets.

# The fact that it does not have any diacritical marks which were introduced around the eighth decade of the first century; hence the manuscript must have been written before that.

# The fact that it does not have the vowelling symbols introduced by Du’ali, who died in 68 Hijra; hence it is earlier than this.

# The fact that it is written on parchment from a gazelle, while later Qur’ans are written on paper-like sheets.

# The fact that it does not have any diacritical marks which were introduced around the eighth decade of the first century; hence the manuscript must have been written before that.

# The fact that it does not have the vowelling symbols introduced by Du’ali, who died in 68 Hijra; hence it is earlier than this.

In other words: two of the copies of the Qur’an which were originally prepared in the time of Caliph ‘Uthman, are still available to us today and their text and arrangement can be compared, by anyone who cares to, with any other copy of the Qur’an, be it in print or handwriting, from any place or period of time. They will be found identical.

The ‘Ali Manuscript

Some sources indicate that a copy of the Qur’an written by the fourth Caliph ‘Ali is kept in Najaf, Iraq, in the Dar al-Kutub al-‘Alawiya. It is written in Kufi script, and on it is written: “Ali bin Abi Talib wrote it in the year 40 of the Hijra’. [17]

Some sources indicate that a copy of the Qur’an written by the fourth Caliph ‘Ali is kept in Najaf, Iraq, in the Dar al-Kutub al-‘Alawiya. It is written in Kufi script, and on it is written: “Ali bin Abi Talib wrote it in the year 40 of the Hijra’. [17]

3. The Qur’an In Print

From the sixteenth century, when the printing press with movable type was first used in Europe and later in all parts of the world, the pattern of writing and of printing the Qur’an was further standardised.

There were already printed copies of the Qur’an before this, in the so-called block-print form, and some specimens from as early as the tenth century, both of the actual wooden blocks and the printed sheets, have come down to us. [18]

The first extant Qur’an for which movable type was used was printed in Hamburg (Germany) in 1694. The text is fully vocalised. [19]Probably the first Qur’an printed by Muslims is the so-called ‘Mulay Usman edition’ of 1787, published in St. Petersburg, Russia, followed by others in Kazan (1828), Persia (1833) and Istanbul (1877). [20]

In 1858, the German orientalist Fluegel produced together with a useful concordance the so-called ‘Fluegel edition’ of the Qur’an, printed in Arabic, which has since been used by generations of orientalists. [21]The Fluegel edition has however a very basic defect: its system of verse numbering is not in accordance with general usage in the Muslim world. [22]

The Egyptian Edition

The Qur’anic text in printed form now used widely in the Muslim world and developing into a ‘standard version’, is the so-called ‘Egyptian’ edition, also known as the King Fu’ad edition, since it was introduced in Egypt under King Fu’ad. This edition is based on the reading of Hafs, as reported by ‘Asim, and was first printed in Cairo in 1925/1344H. Numerous copies have since been printed.

The Qur’anic text in printed form now used widely in the Muslim world and developing into a ‘standard version’, is the so-called ‘Egyptian’ edition, also known as the King Fu’ad edition, since it was introduced in Egypt under King Fu’ad. This edition is based on the reading of Hafs, as reported by ‘Asim, and was first printed in Cairo in 1925/1344H. Numerous copies have since been printed.

The Sa’id Nursi Copy

Finally, the Qur’an printed by the followers of Sa’id Nursi from Turkey should be mentioned as an example of combining a hand-written beautifully illuminated text with modern offset printing technology. The text was hand written by the Turkish calligrapher Hamid al-‘Amidi. It was first printed in Istanbul in 1947, but since 1976 has been produced in large numbers and various sizes at the printing press run by the followers of Sa’id Nursi in West Berlin (Germany).

Finally, the Qur’an printed by the followers of Sa’id Nursi from Turkey should be mentioned as an example of combining a hand-written beautifully illuminated text with modern offset printing technology. The text was hand written by the Turkish calligrapher Hamid al-‘Amidi. It was first printed in Istanbul in 1947, but since 1976 has been produced in large numbers and various sizes at the printing press run by the followers of Sa’id Nursi in West Berlin (Germany).

Comments

Post a Comment